Does not have the features of an asset

FX is not an asset because it hasn’t got that most essential feature of an asset, which is to provide a utility to the asset holder independent of any changes in the price of the asset after its purchase, for significantly long periods of time after its purchase. Without quibbling on this, I would say that when the Average Joe purchases an asset, he hopes to be able to use it for at least 2-3 years, if not a couple of decades.

For instance, a car provides the utility of transport, a house provides the utility of shelter, a factory produces the utility of production and so on. All of these assets are fed with some inputs – car with fuel, house with electricity, factory with raw materials – and they produce the utility they are meant to provide. Their ability to produce utility is dependent on the continued supply of inputs, and not on any extraneous change in the market price of the asset itself. Of course, looking at it the other way round, the market price of an asset can vary in accordance with its ability/ inability to produce the desired utility, but that’s a different point altogether.

Financial assets such as stocks, bonds or bank deposits provide the utility of returns by the very virtue of ownership – either interest in the case of bonds and deposits, or dividend (in most instances) in the case of stocks. These returns are accruable to the owner, irrespective of the changes in the market price of the stocks/ bonds.

The prices of all assets, whether physical or financial, can rise or fall – producing capital gains or losses – but all assets continue to provide, over time, the utility they are supposed to provide, irrespective of these price changes. Yes, all physical assets depreciate with wear and tear, which reduces their ability to provide utility, but that is, as said earlier, another matter.

Currencies do not have this characteristic of assets. Currencies are a means of exchange. They are used to buy assets or commodities. Yes, they do provide a utility – they enable the exchange of goods and services, they enable commerce. But the provision of this utility is dependent on the price of the currency itself, through inflation/ deflation in the domestic arena or through appreciation/ depreciation vis-à-vis other currencies in the international arena. This is an essential difference between currencies and other assets. Further, unlike financial assets like stocks, bonds or bank deposits, the mere possession of currencies does not necessarily provide a return. You would have to make a deposit in a bank to earn interest. Note then, that it is the deposit that earns interest, not the currency itself. Yes, there can be gains or losses due to changes in the price of the currency, but the currency itself produces no returns. As such, it would seem that whatever else currencies might be, they are not assets.

More like a commodity

Perhaps currencies are more akin to commodities? Most commodities, such as fuel, metals, wood, chemicals and others, become useful when used as an input in a productive process. The mere possession of the commodity does not necessarily produce a benefit. Similarly, currencies produce a benefit or utility when used as a means of exchange in trade and commerce and in capital transactions. Further, the holding period for most commodities, especially in the physical form, tends to be short. This is in contrast to assets, which the Average Joe wants to hold for a long period of time. Holding a commodity is seen as holding inventory and no one wants to hold inventory for very long, because there are costs attached to carrying that inventory.

Apart from the cost of storage, the biggest cost of holding commodities is the risk of a fall in prices. Of course, there are chances of prices rising as well, but statistically, the chance of a rise in commodity prices tend to be more or less equal to the chances of a fall over a long period of time. Similarly, the holding of currencies brings with it more or less equal chances of a rise or fall in prices. This is unlike the case of assets (like houses, or factories, or gold or brand name), where the chances of a rise in prices are, in the long run, greater than the chances of a fall. There is, thus, prima facie, a disincentive for most people to hold onto commodities or currencies for very long periods of time, or in excess of their requirements, especially in the physical form.

Of course, an entire industry thrives on the holding of commodities. But, this is usually in the form of futures or options. Here too, we find that the holding period for most futures or options tends to be rather short, especially in comparison with the holding period for even financial assets. The open interest in most Futures markets, for both commodities and currencies, tends to be concentrated in the first three months, with the first month having the highest open interest. People are, for the most part, interested in trading the commodity or the currency, buying and selling it for small profits in short periods of time. Few people tend to hold a commodity or currency futures for periods beyond three months. In fact, a few minutes to a few hours is the norm for the greater number of participants in the currency market. Clearly, therefore, gains in the currency market are in the nature of trading gains (which is a characteristic of commodities), rather than capital gains (which is a characteristic of assets).

Further, it is an oft-quoted fact that the global currency market is the biggest market in the world, with volumes approaching $3 trillion per day. The market for the G7, or Major, currencies is highly liquid and not amenable to “cornering” or “price rigging”. Individual participants in the market have no hope of influencing price. So much so that these days even Central Banks, especially of the G7 countries, have largely given up on the practice of Intervention. The global currency market is the closest that one can ever come to the utopian concept of Perfect Competition in a market, where there are a large number of participants, there is no barrier to entry or exit of participants and everybody shares instantaneous and complete information.

In effect, the global currency market is a wholesale market, the biggest of them all. And, wholesale markets deal in commodities, not assets. We do not find Rembrandts, Picassos, Van Goghs, or Bikash Bhattacharjees being traded in wholesale markets. Maruti 800s, and even Honda Citys, are commodities, when compared to cars like Ferraris and Porsches, leave alone F1 cars.

How does this help?

Alright, suppose the debate is settled, or at least, it is personally settled for me (until someone with better logic unsettles me) that currencies are commodities, not assets, how does that help in generating better returns, or Alpha?

Firstly, we realize that all “returns” in commodity (and currency) trading is Alpha because the commodity produces no returns on its own. Secondly, we can shun some of the techniques of investing in assets, such as “Buy and Hold”. Thirdly, we realize that while all returns in currency trading is Alpha, the Alpha, in turn, is generated from trading. Thus, we start looking for ways of trading better.

We can draw inspiration from the fruit or vegetable seller, whether he be running a small shop, or he be a wholesaler. Both look to make a small margin on each sale and would rather let the stock go at cost than to see it go waste at the end of the day, resulting in a loss. He does not look to, on an average, make more per kilo or ounce sold, than is available in the market at the going price.

Cut to the currency market.

If we act like the fruit seller, we will change our tactics. Instead of trying to figure out things like, “Is the Euro, or the Yen, going to go up or down”, we will try and spend more time working out how much profit per trade is generally possible to achieve. Having known that, we will try and increase the number of trades we do wherein we can get that average profit per trade we are looking for. This will also help us control our greed and we will not mind cutting losses fine and getting out of a trade at a meagre profit, or at cost, or at worst, a meagre loss. Disinvesting ourselves of the notion that we are investors will help us become better Currency Traders and thus help us generate Alpha.

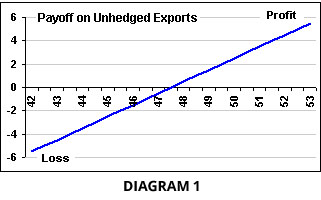

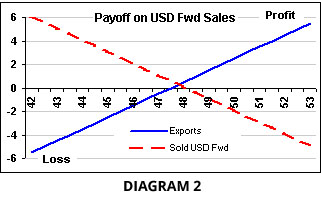

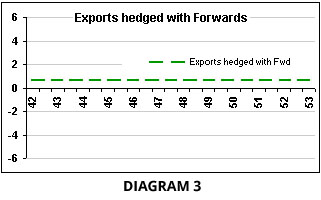

Thus, when a hedge, whose quantum is, say, 30% of the actual underlying exposure, makes money, there is no reason to be overjoyed. Quite obviously, when the 30% hedge is making money, the balance 70% unhedged exposure is losing money. Similarly, if the 30% hedge loses money, that is no reason to crucify the risk manager – the balance 70% unhedged exposure is actually making money. In fact, therefore, if the hedge ratio is less than 50%, a loss making hedge is to be preferred to a profitable hedge.

Thus, when a hedge, whose quantum is, say, 30% of the actual underlying exposure, makes money, there is no reason to be overjoyed. Quite obviously, when the 30% hedge is making money, the balance 70% unhedged exposure is losing money. Similarly, if the 30% hedge loses money, that is no reason to crucify the risk manager – the balance 70% unhedged exposure is actually making money. In fact, therefore, if the hedge ratio is less than 50%, a loss making hedge is to be preferred to a profitable hedge.