RBI risk 172

Jun, 27, 2020 By Vikram Murarka 0 comments

126% RUPEE WEAKNESS and DAMPENING OF INVESTMENTS:

POSSIBLE UNINTENDED CONSEQUENCES OF RBI’S EXCHANGE RATE POLICY

Please click here to download the full PDF Report.

Or, how India/RBI’s policy of weakening the Rupee to promote Exports does not work and can actually harm Investments, Exports and Growth.

Also, the global markets are presenting us with a unique opportunity. We should take it.

26-Jun-20, USDNR @ 75.63

Executive Summary

India/RBI has long followed a policy of weakening the Rupee, ostensibly in an attempt to promote Indian exports and thereby reduce the country’s chronic trade deficit (hereinafter referred to as “the policy”). [Ref I, II].

Several studies have conceded that a weakening currency does very little to promote exports growth, yet we persist with the policy. Alarmingly, not only has this policy not delivered export growth, it now threatens to severely damage India’s ability to raise foreign capital that is so vital for the massive investments that the country needs.

Further, since August 2019, the RBI is actively creating a one-way-street in the forex market, where only Rupee depreciation is allowed, not Rupee appreciation. This can have disastrous results in that, if pushed beyond a point (which is very close by), the Rupee could weaken by 126% over the next decade. The situation is dire and there is very little room for policy error here. The RBI would do well to forthwith abandon its old policy of weakening the Rupee in a one-way manner and leave the exchange rate to its own devices, else it could be courting disastrous consequences.

Ironically, the global market conditions are currently presenting India with a unique never-again opportunity to enter into a virtuous cycle of strong/ stable currency – higher investments – higher exports – higher growth, all with lower inflation and lower interest rates. This can either be capitalized on by leaving the exchange rate alone, or it can be frittered away by engineering perpetual Rupee weakness, with disastrous consequences.

Contents

Section A: Evidence Refutes Policy

I. FX Rate does not influence Exports, nor does it impact Imports

II. Exports respond to Investments, rather than to the Rupee

III. IIP and FX Reserves – another albatross around the Rupee’s next

Section B: The Policy Side Effects

IV. Rupee weakness can impede Investments – warning from the Sensex

V. Impairing the market’s shock absorbing capacity

Section C: The Future Outlook

VI. Opportunity presenting itself – should be capitalized on

VII. A bright future is possible. Please do not commit Hara-kiri.

VIII. Progression or Regression – two possibilities

APPENDIX: China and Japan: Currency and Exports have weak correlation

References and Data Sources

Ref I. Yin-Wong Cheung and Rajeswari Sengupta: It is perceived that the Reserve Bank of India adopts an asymmetric intervention policy that stems a currency appreciation whereas allows a reasonable amount of depreciation.

Ref II C. Rangarajan & R. Kannan: The stated policy of the Reserve Bank is that it has no specific target and that it intervenes only to reduce volatility. This is only partially true.

SECTION A – EVIDENCE REFUTES POLICY

I. FX Rate does not influence Exports, nor does it impact Imports

Contrary to popular belief that a weakening currency leads to exports growth, data and research [Ref I, III] show that this is not so. Rather, the opposite correlation seems to hold truer in India since 2000.

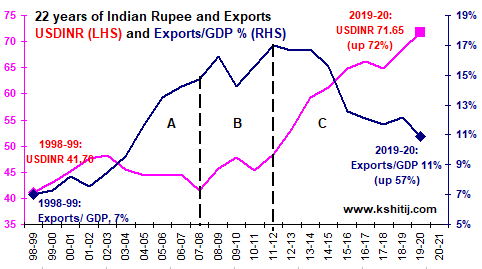

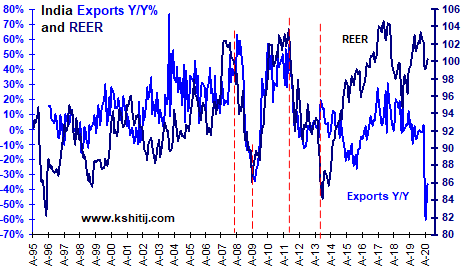

Fig 1: 22 years of USDINR and Exports/ GDP

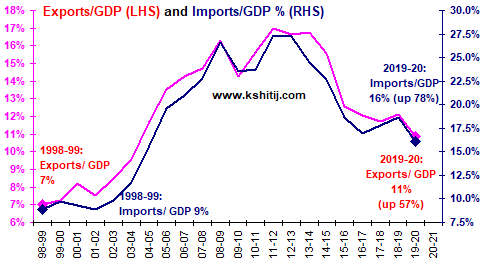

The USDINR (left axis) has weakened 72% from 41.70 in 1998-99 to 71.65 (average) in 2019-20.

In this period, Exports/ GDP (right axis) has risen only 57% from 7% in 1998-99 to 11% in 2019-20. This period can be divided into sub-periods A, B and C. Periods A and C show that the policy in question does not work. These are examined below.

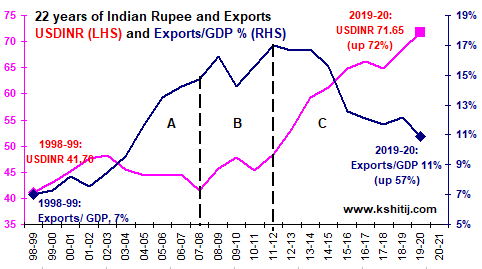

Table 1: USDINR and Exports/GDP movement in India

It is only in Period B (a short interlude of 3 years from 2008 to 2011) that the theory seems to work. In the longer timeframe of Period A (8 years) and Period C (9 years), export performance is actually seen to be contrary to what might be expected if the theory were correct.

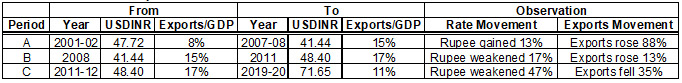

Fig 2: REER also does not work

India’s annual Exports growth (left axis) showed steady improvement since 1996, more so after 2000. During the period, the Real Effective Exchange Rate (REER, right axis) went from an undervalued level of 82 to an overvalued level of 102. Later, even as the REER became undervalued, exports fell and again thereafter, even though the REER became overvalued, exports rose. If anything, the REER and Exports correlation is opposite to that expected as per theory. [Ref I]

Ref I. Yin-Wong Cheung and Rajeswari Sengupta: …starting from 1993-94 onwards, the expected relationship seems to have been reversed… Indian exports grew rapidly since 2000 despite the REER appreciation…

Ref III. Spyros Roukanas, Persefoni Polychronidou, Anastasios Karasavvoglou: Statistical data on real effective exchange rate and aggregated data of Serbian exports indicate that the ambience of overvalued national currency did not harm export performance.

One might think that perhaps the exchange rate policy is expected to curb the trade deficit by curbing Imports. After all, a stronger Rupee (2001-08) was accompanied by higher Imports and later a weaker Rupee (2011-20) saw a fall in Imports. However, this behaviour of Imports is because it has a symbiotic relationship with Exports, as seen below. [IV]

Fig 3. Exports and Imports move together

Exports and Imports move up and down together closely. This is because (a) over the years, the import content of India’s exports has risen and (b) both exports and imports are impacted more by the global trade climate than by the exchange rate. [Ref II]

This relationship between export-import is observed in China and Japan also.

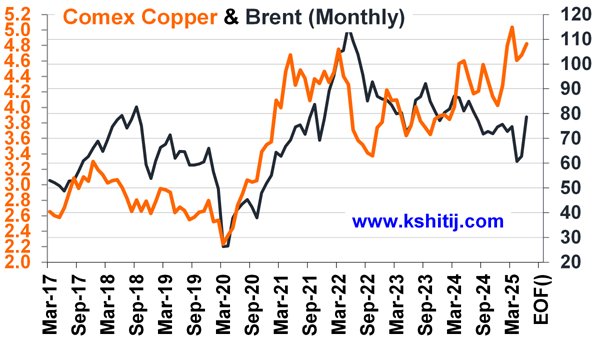

Fig 4. Exports and Imports move with Brent prices

We just saw how Exports and Imports move together. Here, we see that, As might be expected, India’s Imports and Brent Crude prices increase/ decrease together.

Therefore, India’s Exports, Imports and Brent Crude prices all move together.

This is because Crude prices can be taken as a barometer of global trade and GDP growth and it is this which impacts Indian exports/ imports more rather than the Dollar-Rupee exchange rate. [Ref II]

From the evidence so far, we can surmise that the policy of weakening the Rupee to promote Indian exports and narrow the trade deficit has not worked.

Ref II: C. Rangarajan & R. Kannan: The import content of India’s exports has risen from 9.4% in 1995 to 24% in 2011; we find that World Exports has a more powerful effect in influencing exports than REER. World Exports account for 83% of the variability as against 17% of REER

II. Exports respond to Investments, rather than to the Rupee

It is well known that Exports are positively impacted by investments in infrastructure (ports, roads, power et al) and production capacities (large scale factories), because these go much further in enhancing a country’s export competitiveness in the world market rather than a weakening currency. The data bears this out.

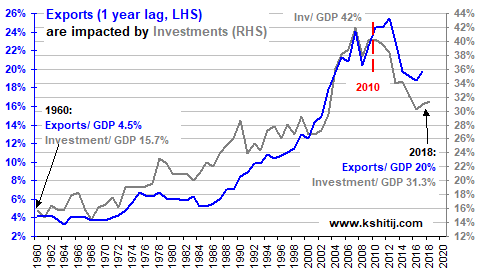

Fig 5. Exports are related to Investments

As Investment/ GDP grew from 15.7% in 1960 to 42% in 2007, Exports/ GDP also rose from 4.5% to 21%.

In this period also, investments grew faster from 1984 to 2007 as compared to earlier, and exports also picked up speed in line with investments.

After 2010, the Inv/GDP ratio fell to 31.3% and along with it, Exports/ GDP also fell to 20%.

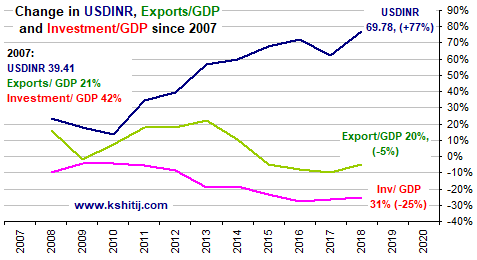

Fig 6. Rupee weakened 77%, yet Exports fell 5%

This chart zooms into the period after 2007.

We find that by 2018, the Rupee had weakened 77% compared to 2007. Yet, in this period, Exports fell by 5%. This again clearly shows that the exchange rate has no impact on Exports.

Rather, Exports fell in line with the 25% decline in the Investment/ GDP ratio.

Exports competitiveness and growth in the world market is a complex thing. It depends on a number of factors including infrastructure, quality, global demand, marketing, research and development, enabling legal system, labour productivity, economies of scale and so on. It is simplistic to think that Export growth can be increased by weakening the currency. If anything, it is better to aim to promote Investments as a means to achieve Exports growth. [Ref II]

We should be warned that weakening the Rupee in pursuit of an empty theory can jeopardize Investments, the single most important factor contributing to higher exports and GDP growth. The exchange rate may be left to its own devices.

Ref II: C. Rangarajan & R. Kannan: Truly speaking, the critical factor is not so much exchange rate as competitiveness… the exchange rate variable represents more than the pure exchange rate. It really stands for the degree of competitiveness of Indian exports… The crucial factor is not so much exchange rate as competitiveness. The whole gamut of policy measures government introduces from time to time are aimed at this objective. We have not been able to take into account explicitly this factor. Exchange rate is one element in this basket of measures.” [Author’s observation: inability to measure the competitiveness of Exports and positioning the exchange rate as a proxy for it is leading to a grave policy error, which should be stopped forthwith].

III. IIP and FX Reserves – another albatross around the Rupee’s next

Another argument put forth to support the policy of weakening the Rupee is that the RBI needs to build its FX Reserves as a counterbalance to India’s Net International Investment Position.

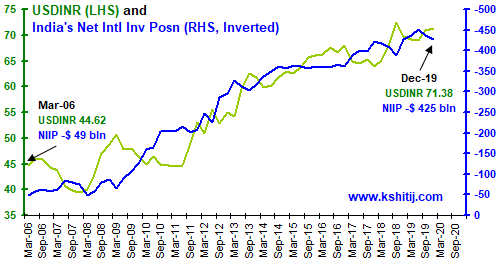

Fig 7. Weakening the Rupee with NIIP

India’s Net International Investment Position (NIIP, right hand axis, inverted) has “deteriorated” since 2008 as India’s economy has been increasingly opened to international capital flows. As can be seen, the Rupee has weakened alongside.

In a manner, a deteriorating NIIP can be seen as a “risk” and a cause for concern. However, it is a given that the NIIP will continue to “deteriorate” over time, as India’s need for foreign capital will only keep on increasing and that FX Reserves will never catch up or limit the growth of the NIIP. If the RBI continues to buy Dollars to increase FX Reserves “war chest”, then the Rupee can weaken into perpetuity.

Increased Dollar buying since Aug-2019. Why?

The RBI has significantly increased its Dollar purchases since August 2019 [See Section B-V], forcibly preventing Rupee gains even in the face of robust capital inflows. While RBI purchasing Dollars is not new, what we now see is that the RBI is intervening not to smoothen out volatility but to actively prevent Rupee appreciation. This is a new phenomenon and seems to be somehow linked to the adoption of the new Economic Capital Framework (ECF) after Aug-2019, although we do not clearly understand how and why.

FX Reserves form 73% of the RBI’s balance sheet. To quote from the August 2019 report of the Expert Committee to review the extant ECF, “… the RBI suffers losses when the rupee appreciates against the USD and/ or the other currencies in its forex portfolio and it gains when the rupee depreciates against them. Thus, counter-intuitively, the RBI suffers valuation losses during times when the economy is witnessing strong growth and large capital inflows which normally are associated with rupee appreciation.”

The accumulated revaluation profits over the years makes up the Revaluation Reserves of the RBI. By including this in the Contingent Risk Buffer (CRB) of the RBI, the CRB stood at 26.8% of the RBI’s balance sheet (on 30-Jun-18), well in excess of the 6.5% level recommended to meet various risks faced by the RBI. Excluding the Revaluation Reserves, the CRB stood at 7.2%, still in excess of recommended 6.5%.

The Expert Committee to review the extant ECF has recommended that the Revaluation Reserves should be retained with the RBI and should not be alternatively deployed or distributed (say by way of dividend to the Government). It is perplexing then, as to why the RBI is continuing to increase its Reserves.

The only explanation seems to be that apart from the possibility that it wants to avoid revaluation losses due to Rupee appreciation (?), it also seems that it is acutely sensitive to “financial stability risks”, especially after the GFC. In the words of the Expert Committee, “financial stability risks are those rarest of the rare, fat tail risks whose likelihood can never be ruled out and whose impact can be potentially devastating.”

The question that arises is, could the dogged building up of Reserves as a foil against such risks actually end up inviting the far away risk closer, so close that it actually materializes? The danger is that Rupee weakness beyond .........

Continued in Section B and Section C. Please click here to download the full PDF report.

Array

In our last report (29-May-25, UST10Yr 4.45%) we had stuck to our previous forecasts, calling for the US2Yr to dip to 3.2% and the US10Yr to 3.6%. Although those levels are …. Read More

Brent rose sharply from $58.20 itself instead of extending the fall to our expected $55, meeting our long-term target of $70 much sooner than expected. The acceleration in crude prices have been triggered by … Read More

The Dollar Index has high chances of rebounding from support at 96, in which case, it could limit the immediate upside for Euro and lead to a decline in the coming months …. Read More

Our July’25 Dollar-Rupee Quarterly Forecast is now available. To order a PAID copy, please click here and take a trial of our service.

Our July ’25 Dollar Rupee Quarterly Forecast is now available. To order a PAID copy, please click here and take a trial of our service.

- Kshitij Consultancy Services

- Email: info@kshitij.com

- Ph: 00-91-33-24892010

- Mobile: +91 9073942877