Challenging Basic Forex Risk Management Concepts

Sep, 09, 2008 By Vikram Murarka 0 comments

At a time when there has been a big jump in risk aversion in global financial markets, this article challenges two revered canons of forex risk management. The article will first build a case that companies should actively manage currency risk, which is otherwise viewed as a “necessary evil”. Second, it will argue that the concept of “natural hedge” goes against the basic tenets of profit maximization for companies and highlight an example where it was profitable for a company to shun a natural hedge even when it theoretically existed.

While preparing to write this article, I was assailed by a bit of self-doubt. Was I a fool, rushing in where angels feared to tread? It was heartening to find that mine was not the lone voice in the woods.

An article entitled “To Hedge or Not to hedge”, cited in GT News on 01-Aug-2006 quoted James Binny, executive director of ABN AMRO's FX analytics and risk advisory, as saying, “It is accepted now that you can make money out of currency and it should be a useful part of the portfolio." The article went on to conclude that “ the idea that FX transactions will cancel themselves out over time is one that is antiquated , and few are still prepared to leave anything to chance and ignore this opportunity to trade.” (Italics are mine).

World without theories

Let us go back to the genesis, to a time when there were no theories regarding forex risk management on Planet Earth. We consider the example of a diamond company, domiciled in India , which imports uncut diamonds, invoiced in US Dollars. It cuts and polishes the diamonds and exports them back, invoicing the exports in US Dollars.

|

|

As the charts above show, the company, as an Importer, has an obligation to buy Dollars, which is the same as running a Short position in USD-INR (Fig 1). As an Exporter, it holds a Long position in the export Dollars that it needs to sell (Fig 2). This is the true picture of its foreign exchange exposures, shorn of any theories.

What should the diamond company do? Continuing to live in a world without theories, the company would attempt to buy its Import Dollars (or cover its original “Short” position) at a low rate and at the same time it would want to sell its Export Dollars (or cover its original “Long” position) at a higher rate. Suppose, the company is indeed able to buy Dollars at 42.00 and to sell Dollars at 44.00, it would have captured a net Export-Import margin of INR 2.00 per USD, or 4.65% (2/43) for itself from the foreign exchange market.

Forex is not my business. Is that really so?

This 4.65% net margin is the result of judicious management of the forex rates that the company pays and receives, not from the core business of polishing uncut diamonds. Is there anything wrong in trying to capture this profit? In a competitive world, every variable that a business is exposed to needs to be managed with the intent of adding to shareholder value. Forex is no exception.

Conventional wisdom says that foreign exchange trading is not the business of a manufacturing company. While one agrees that forex “trading” is not the core business of the company, it is an undeniable fact that the Imports and Exports undertaken in the course of its core business, forces the company to initiate “trades” in the forex market, as demonstrated by Figs 1 and 2 referred to earlier. This fact, as deduced by native logic, flies in the face of established convention, that “forex is not my business”.

A steel manufacturer, although not in the freighting business, tries its best to keep its freight costs down, both while transporting raw materials to its plants and while shipping finished goods out. A car manufacturer, although not a banker, makes all efforts possible to procure working capital at the cheapest possible rates. Thereafter, very legitimately, it tries to deploy any surplus funds that it might have available, at the highest rates possible. Of course, without exposing the company to risk. Variables such as freight, capital and labour costs are integral to each and every business and it is the management's duty to manage these variables efficiently, and if possible, profitably.

Similarly, although the diamond company in our example might not have wished the forex trades on itself, it does have an obligation to profitably manage the trades it has on hand.

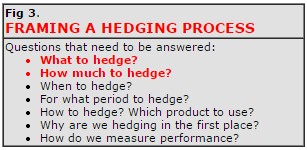

The process of managing the trades is called hedging. It involves framing the answers to the questions listed in the box alongside, and acting accordingly.

The process of managing the trades is called hedging. It involves framing the answers to the questions listed in the box alongside, and acting accordingly.

We focus on the first two questions, viz. “What to hedge?” and “How much to hedge?” Continuing in the same vein of using unsullied thought, the answer would have to be that both imports and exports should be hedged, and should be hedged in their entirety (not necessarily all in one shot, though), because these are, after all, the company's original forex trades, and need to be covered .

Natural Hedge? I want a margin!

Conventional wisdom, however, says that since the company has both Imports, on the one hand, and Exports on the other hand, it has a “natural hedge” and needs to hedge only the residual net exposure, or excess of exports over imports. Say, the company imports diamonds worth USD 100 and exports diamonds worth USD 110. Conventional wisdom would ask the company to hedge/ sell only USD 10. Doing that, however, would mean that it should not try to earn an Export-Import Margin from forex on USD 100. At the most it may attempt to earn a forex margin on USD 10. But that would not really be worth writing home about, would it?

Thankfully, there is enough literature that agrees that a “natural hedge” exists only in theory, given the realities of time and amount mismatches. Even if we assume a situation where the utopian concept of “natural hedge” does exist, a profit-seeking company would still want to buy Dollars for its imports at a lower rate and to sell its export Dollars at a higher rate.

What would you think of a grocer who displays a rate list like the one shown alongside (Fig. 4)? Every grocer seeks to be compensated by the customer for taking the trouble of bringing the goods from the wholesaler to a well appointed store in the neighbourhood, for the convenience of the customer. Similarly, the diamond manufacturer would want to secure a reward (difference between its export-import rates) for the currency risk it carries on the entire USD 110, not only on USD 10.

Text Books have not been updated

A bulk of the forex risk management theory in vogue and practice today dates back to the eighties and early nineties (a time when the forex market itself was no more than 15-20 years old) and emanates from bank dealing rooms. It was a time when there were a number of currencies in circulation in Europe , when bid-offer spreads used to be wide and volatility used to be high. Banks did indeed find some positive and negative flows canceling each other out. While managing a mess of several currencies, the banks found it easier to deal with the residual currency amounts. It probably made sense at that time when computers, communication and information systems were less powerful than they are today.

When companies, who were then totally new to tackling currency risk, turned to banks for guidance, the banks simply handed out a manual of what they themselves did, to their clients. Here, it must be remembered that, by nature, banks are risk averse – they seek coverage and collateral at the very outset for the money they lend. Manufacturing companies, on the other hand, thrive by taking risks. “Fortune favours the brave” has been the mantra of all entrepreneurs across time and space.

Further, the eighties and early nineties were times when globalisation and competition were not as fierce as they are today. Profits were easier to come by and companies could afford to leave a few stones unturned during their quest for profits.

Not so today. Times have changed and the textbooks need to be updated. Business competition has increased in general as also in the forex market. Why, Bid-Offer spreads are now down to a few “piplets”, even at the retail level! At the same time, currency volatility has reduced substantially and even George Soros might find it difficult to do an encore of his famous “broke the BOE” trade. Information systems are more robust and real time. In this new environment, there is both a possibility and a need for companies to try and work currencies for their bottomlines, rather than thrusting their heads into the sand like ostriches.

Is it worth it?

Can it really be worthwhile to go against an established belief, to do something radically different? Should the diamond company with a natural hedge really try to adopt a policy of “gross” hedging, rather than “net” hedging? Let the numbers do the talking.

We had worked with one such company, using our proprietary concept of “Dynamic Benchmarks”. We did not go by the “natural hedge” concept and instead, hedged both the imports and exports separately. We used only plain vanilla hedging tools as Forwards and Puts/ Calls. Most importantly, we did not expose the company to any additional risk at all. The average hedge ratio was in the region of 56%.

Over the period Apr-06 to Jan-08, even as the Indian Rupee appreciated against the US Dollar, Exports were covered along the Green line shown in the chart alongside (Fig 5). At the same time, Imports were hedged along the Red line, benefiting from the very same appreciation of the Rupee.

As a result, the company earned a very handsome Export-Import margin – from forex – over and above its normal business.

As seen in the table alongside (Fig 6), net Export realizations, after hedging costs/ benefits, averaged INR 45.56 per USD in the financial year Apr-06 to Mar-07 and averaged 43.30 in FY 07-08. Net Import costs, after hedging costs/ benefits, averaged 45.28 in 06-07 and 40.96 in 07-08, leaving an Export-Import margin of 0.6% and 5.7% in FY 06-07 and 07-08 respectively. Very satisfactory results – achieved by going against the grain of “natural hedge” – without taking risks or speculating.

The times they are a-changin'

As I finish writing this article, I have before me the views of some of the leading CFOs and Treasurers in Corporate India, as featured in the 06-Sep-08 issue of Outlook Business. Mr NS Paramasivan, Global Treasury Head, Essar Group, for instance, say, “Our mandate is to lower the cost of imports as much as possible and increase the realization on exports as much as possible.”

And there's nothing wrong with it, really, as long as it is done systematically and responsibly, without exposing the company to undue risk. And, when Mr YM Deosthalee, CFO, L&T says, “We have the ability to convert our treasury to a profit center. But we have no plans to do it yet”, it seems all that is needed now is for the academic intelligentsia to concede that trying to manage forex cost efficiently, perhaps profitably, is not a business crime. Indeed, it is just another avenue to be strenuously explored in the overall interests of creating shareholder value.

This article, authored by Vikram Murarka, has been commissioned by GTNews.com, a leading website on Treasury and Finance related issues

Array

In our last report (29-Dec-25, UST10Yr 4.12%) we had said the US2Yr could fall to 3.00%. However, contrary to our expectation, the US2Yr has moved up. The US10Yr has also risen, much earlier than …. Read More

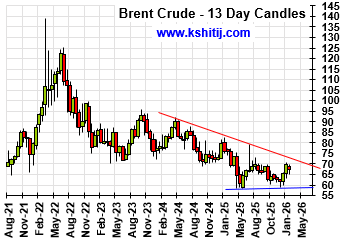

Having risen sharply in Jan-26 to $70.58, will Brent again rise past $70 and continue to rise in the coming months? Or is the rise over and the price can move back towards $60? … Read More

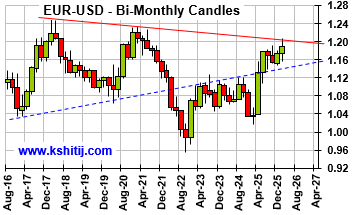

Euro unexpectedly reached 1.2083 in Jan-26 on Dollar sell-off but recovered quickly back to lower levels. Will it again attempt to rise targeting 1.24? Or will it remain below 1.20/21 now and see an eventual decline to 1.10/08? …. Read More

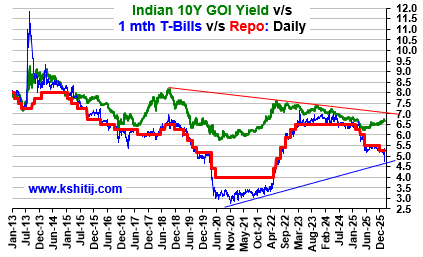

The 10Yr GOI (6.6472%) had risen to a high of 6.78% on 01-Feb. It has dipped a bit from there but has good Support at … Read More

In our 10-Dec-25 report (USDJPY 156.70), we expected the USDJPY to trade within 154-158 region till Jan’26 before eventually rising in the long run. In line with our view, the pair limited the downside to … Read More

Our February ’26 Dollar Rupee Monthly Forecast is now available. To order a PAID copy, please click here and take a trial of our service.

- Kshitij Consultancy Services

- Email: info@kshitij.com

- Ph: 00-91-33-24892010

- Mobile: +91 9073942877